Here is a quick guide on differentiating consolidations vs atelectasis on chest x-ray.

The reason that we can differentiate structures on x-rays is due to differences in density. For example, the lungs are air-filled and appear black whereas the ribs, vertebrae, and heart are solid and appear white.

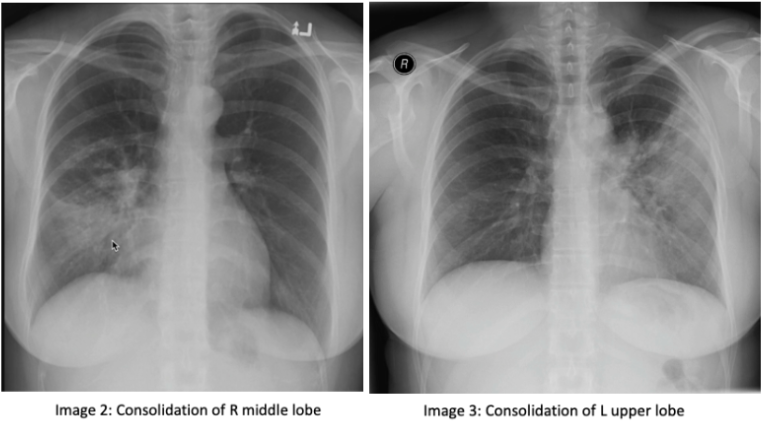

Consolidation: consolidation represents the replacement of alveolar air with fluid, blood, pus, or other substances. There are 3 lobes of the right lung, the upper, middle, and lower lobes. The right middle lobe sits next to the heart border. The left lung has 2 lobes, the upper and lower lobe. The left upper lobe sits next to the heart (image 1). If you have an obscured right heart border, it may indicate consolidation of the right middle lobe (image 2). Similarly, an obscured left heart border may indicate a consolidation in the left upper lobe (image 3). The lower lobes of each lung sit next to the hemidiaphragm. If you cannot make out a hemidiaphragm, it may suggest that there is something of similar density, such as a consolidation, in that lower lobe.

On a normal lateral chest x-ray, the vertebrae should get progressively darker as you get closer to the bases, known as the "more black sign". The vertebrae located near the apex of the lung have overlying muscles, making them appear white, compared to those at the bases that have overlying air, which makes them appear darker (image 4). You should also be able to make out 2 hemidiaphragm on the lateral x-ray with sharp costophrenic angles.

Atelectasis: Atelectasis refers to the collapse of a lung portion. On a normal x-ray, ⅓ of the heart is located on the right and ⅔ of the heart is located on the left side of the chest (image 5). In atelectasis, you will see the mediastinum shift towards the affected side due to volume loss, causing the heart and trachea to shift (image 6). In addition, the unaffected lobe on the ipsilateral side will be hyperlucent as a result of compensatory hyper-expansion. The rib spaces on the affected side may also be closer together when compared to the contralateral side and there may be an elevation of the ipsilateral hemidiaphragm.

Tip: don’t be fooled by a rotated cxr. Rotation can be assessed by measuring the distance between the medial edges of the clavicles to the vertebral spinous processes. They should be equal or near equal.

Thanks for reading!

Ariella

References:

https://radiopaedia.org/courses/emergency-radiology-course-online/pages/1417