Anyone else start getting that dusty, musty smell from the heater in your apartment running for the first time since spring? Anyone get headaches with that must? Nausea, confusion? Syncope?

The prehospital protocol for carbon monoxide poisoning is primarily about recognition. Some services may carry CO monitors that can measure a patient’s SpCO, much like a pulse oximeter, but the more important thing is to have a healthy clinical suspicion for it the same way you would in the ED. Often, these crews will be responding to the scene of a fire, or where a CO detector has gone off, so ensuring scene safety is obviously the other crucial part of this approach.

Speaking of fires, what other considerations do we have for EMS when flames are involved? Stay tuned to find out! www.nycremsco.org or the protocol binder until then.

Dave

- POCUS

- Orthopedics

- Procedures

- Medications

- Pharmacology

- Respiratory / Pulm

- Infectious Disease

- Ophthalmology

- Airway

- Obstetrics / Gynecology

- Environmental

- Foreign Body

- Pediatrics

- Cardiovascular

- EKG

- Critical Care

- Radiology

- Emergency

- Admin

- Nerve Blocks

- DVT

- Finance

- EMS

- Benzodiazepines

- Neurology

- Medical Legal

- Psychiatry

- Anal Fissure

- Hemorroids

- Bupivacaine

- Ropivacaine

- EM

- Neck Trauma

- Emergency Medicine

- Maisonneuve Fracture

- Diverticulitis

- Corneal Foreign Body

- Gabapentin

- Lethal Analgesic Dyad

- Opioids

- Galea Laceration

- Dialysis Catheter

- Second Victim Syndrome

- Nasal Septal Hematoma

- Nephrology / Renal

- Hematology / Oncology

- Dental / ENT

- Dermatology

- Endocrine

- Gastroenterology

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- May 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

POTD: Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

POTD: Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

Happy Sunday everyone. Hope you had your fill of Thanksgiving, turkey, football, relatives, and political disagreements over the dinner table. Today I want to delve into a topic that I feel like we encounter relatively regularly in the ED. Let me set the scene: You’re walking into the South Side 7 PM shift, through the ambulance bay doors, hot coffee in one hand and a large and refreshing bottle of San Pellegrino Mineral Water in the other. Stepping through the triage area you first hear- then see- our patient. A young person, actively retching to a volume audible from the waiting room, clutching a kidney basin for dear life. They usually are with a concerned loved one who is rubbing their shoulder for comfort. One quick look and you can size them up- this person looks ill and uncomfortable, but not sick. We’ve all been there. With a new feeling of empathy for this person’s exceptionally vocal nausea, you mosey on to the doctor’s station to await sign-out from your eager and exhausted colleagues. Another beautiful night on South Side- better have 3 In 1 on speed dial for some munchies.

The patient encountered is suffering from cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Cannabis has been used as a medicine for centuries. As legislation in many states in the USA eases restrictions on its use (as of March 31, 2021, it is legal for adults 21 and older to possess up to three ounces of cannabis for personal use in New York), we are seeing more and more patients appearing in the ED presenting with the relatively rare side-effects from marijuana, including hyperemesis. Ironically, cannabinoids are used very commonly to treat nausea and vomiting, particularly in patients with chemotherapy-related symptoms, or patients with cyclic vomiting syndrome. Theoretically, this paradoxical illness is caused by highly potent THC that effects genetically predisposed individuals by differentially downregulating CBD receptors and causing autonomic dysfunction. There is speculation that there is a dose-dependency, and that a biphasic mechanism of action of THC may have anti-emetic effects at low doses, but pro-emetic at higher doses. Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 are the main receptors for THC, one of the main active substances in marijuana. The theory is that the CB receptors in the medulla are responsible for anti-emetic properties, but the CB receptors in the GI tract are the source of dysregulation. There is another theory that the TRPV1 receptor (transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1), which is activated by marijuana, capsaicin, and heat, is altered by chronic marijuana use. It is speculated that the reason patients with CHS take repetitive hot showers is to upregulated the TRPV1 receptor.

Diagnosis

While no diagnostic criteria currently exist for definitive CHS diagnosis major characteristics patients typically display are:

History of regular cannabis use (100% Sensitivity)

Cyclic nausea and vomiting (100%)

Generalized, diffuse abdominal pain (85.1%)

Compulsive hot showers with symptom improvement (92.3%)

Symptoms resolve with marijuana use cessation (92.3%)

A higher prevalence in males (72.9%)

Often patients will experience three phases of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome (3,8):

The Pre-emetic or Prodromal Phase:

Can last for months or years

Characterized by diffuse abdominal discomfort, feelings of agitation or stress, morning nausea, and fear of vomiting

May also include autonomic symptoms like flushing, sweating, and increased thirst

Often have increased use of marijuana to treat these symptoms

Hyper-emetic Phase:

24-48 hours

Multiple episodes of vomiting

Diffuse, severe abdominal pain

Recovery Phase:

Begins with total cessation of cannabis

Often patients require a bowel regimen, IV fluids, and electrolyte replacement

Resolution of symptoms may take up to one month

Common complications of CHS include electrolyte disturbances, dehydration or AKI, and muscle cramps or spasms. Life threatening complications that have been documented include pneumomediastinum from ruptured esophagus, and electrolyte derangement causing seizure or arrythmia. Patients with suspected CHS should be offered counseling, resources, and follow-up for marijuana cessation. Treatment in the symptomatic phase involves symptomatic treatment and pharmaceuticals. It is often necessary to take a multi-faceted approach by giving dopamine antagonists, antihistamines, serotonin antagonists, antipsychotics, and topical capsaicin. Capsaicin is thought to work by transiently activating TRPV1 (which remember, is speculated to be downregulated by chronic marijuana use, and is thought to be the reason for the relief from incessant hot showering). It is a cream that can be applied to the fatty areas of the backs of the arms and abdomen up to 3 times daily, and is available in concentrations from 0.025% to 0.15%.

Pearls

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome is increasing in frequency in the United States.

CHS is characterized by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and chronic cannabis use.

Consider CHS diagnosis in patients with recurrent presentations and negative abdominal pain work-ups.

Avoid opiates for CHS treatment.

Consider capsaicin cream, benzodiazepines, antiemetics and antipsychotics for treatment of CHS

Hope this was informative, and that everyone had a great weekend. See you in the ED this week.

Mak Sarich MD

References: http://www.emdocs.net/more-than-a-hot-shower-treatment-for-cannabinoid-hyperemesis-syndrome-chs/

POTD: Decompensated CHF - a deep dive

This is probably bread and butter for us at Maimo and we are roughly familiar with how to manage it. Today, we take a deep dive into the classification and etiology of decompensated CHF to better understand the disease process. And then a short review on the basics of management just go through it systematically.

What is decompensated heart failure?

When something structural or functional happens to the heart, leading to inability to eject and/or accommodate blood within physiological levels.

Leads to a functional limitation

Requires immediate intervention

2 different scenarios:

1) New-onset acute CHF

No prior history or symptoms of CHF

Triggered by:

Acute MI

Hypertensive crisis

Rupture of chordae tendineae

Usually more prominent pulmonary congestion > systemic congestion

Usually normal blood volume

Treatment focused on treating underlying cause

High dose diuretics less helpful

2) Decompensated (chronic) CHF

Worsening of symptoms in existing CHF

Most commonly caused by:

Low treatment adherence - med noncompliance or poor diet (high salt)

Infection

PE

Tachy/bradyarrhythmias

Often new-onset afib

Factors indicating poor prognosis in DHF:

Pts with BUN > 90 and Cr > 2.75 on admission have a 21.9% risk of in-hospital mortality

Age (above 65 years)

Hyponatremia (sodium <130meq/L)

Impaired renal function

Anemia (hemoglobin <11g/dL)

Signs of peripheral hypoperfusion

Cachexia

Complete left bundle branch block

Atrial fibrillation

Restrictive pattern on Doppler

Persistent elevation of natriuretic peptides levels despite treatment

Persistent congestion

Persistent third heart sound

Sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation

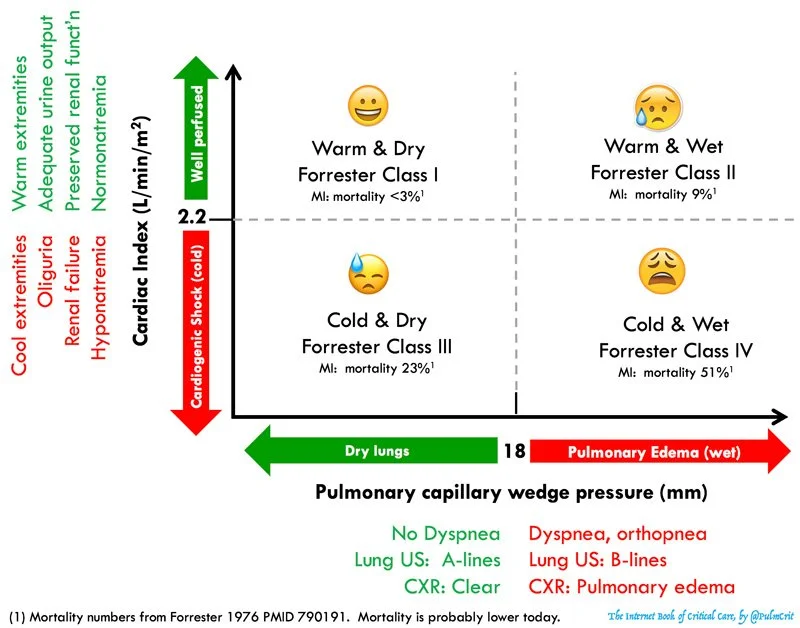

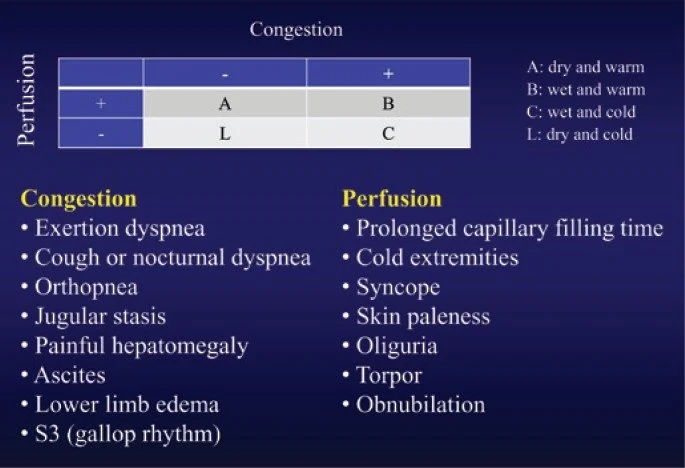

Classification system - Stevenson Classification (below)

Here’s another similar classification chart that’s more visually stimulating:

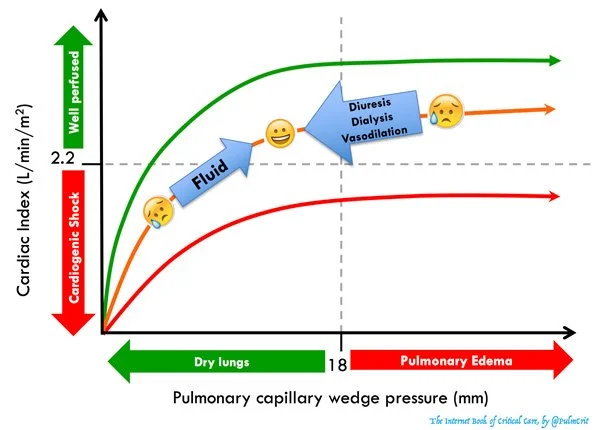

Forrester Classification (below)

Use to guide management

A (dry, warm) = compensated

B (wet, warm) = most common

Vasodilators and diuretics

Consider inotropes especially when SBP b/w 90-120

C (wet, cold) = worst prognosis

Ionotropes and diuretics

IV vasodilators if BP is being intensively monitored

L (dry, cold) = rare

Volume resuscitation +/- inotropes

Causes of CHF exacerbation

Tsuyuki et al, 180 pts

Most common primary cause: excessive salt intake (15%)

Noncardiac disorders (15%)

Inappropriate reductions in CHF therapy (9%)

Ghali et al, 101 pts at Cook County Hospital in Chicago

Lack of compliance with diet, drugs, or both (64.4%)

Uncontrolled HTN (43.6%)

Cardiac arrhythmias (28.7%)

Opasich et al, 161 pts referred to CHF service at Italian hospital

Arrhythmias (24%)

Infection (23%)

Poor compliance (15%)

Angina (14%)

My takeaway: there is wide variability in the causes of DHF and limited studies out there about the various causes. Given that poor medication / diet compliance is often at the top of the list, it seems like good patient education may go a long way in preventing CHF exacerbation. Consider taking the time to really get at why your patient is in CHF exacerbation. Do they not understand how often they’re supposed to take their diuretic? Are they in denial about junk food intake?

You MUST understand the classification of your patient’s CHF in order to manage them appropriately. It’s not always cookie cutter diuretics.

I also decided to touch on basics of CHF management because I thought this was a nice review by emcrit.

1. Treat the lungs

BIPAP - reduce preload and afterload (like ACEI)

Intubation - cardiogenic shock

Drain large pleural effusions if causing respiratory distress

Inhaled pulmonary bronchodilator - epoprostanol or NO

2. Optimize MAP - reduce afterload if pt can tolerate

High dose nitroglycerin - up to 200-250 mcg/min

Transition to oral once stabilized - ACEI, ARB, hydralazine + isosorbide dinitrate

Manage hypotension with pressor - NOREPINEPHRINE IS KING

EPI is reasonable if reduced EF, hypotensive, with poor cardiac output

AVOID dopamine - evidence of harm compared to NE in SOAP-II trial

3. Optimize volume status

Fluids?

End organ perfusion (AKI)

NO evidence of pulmonary congestion (no B lines on US)

Appears truly hypovolemic (no systemic congestion)

Give small boluses at a time and reassess

Diuresis?

SIgnificant pulmonary or systemic congestion

Overall appears hypervolemic

4. Inotrope for HFrEF

Very temporary improvement in hemodynamics and actually associated with worse outcomes in some studies

Inotropes should ONLY be used if:

Hypoperfusion with low-normal BP (like AKI with poor UO despite above interventions)

Refractory cardiogenic pulmonary edema (like if the interventions above don’t work and you still need to reduce pulmonary congestion)

Dobutamine?

Shorter half life, more titratable than milrinone

Preferred for immediate stabilization of very ill patient, someone with marked pulmonary edema on the verge of intubation

Milrionone?

More effective vasodilation than dobutamine

Renally excreted so tricky to titrate dose in renal failure - half life 2.3 hours in normal kidneys

DIgoxin?

The only positive inotrope that doesn’t correlate with increased mortality

Consider for patients with long standing afib and systolic HF

Not front line

5. Treat underlying cause

New onset tachyarrhythmia - convert to sinus. Beware slowing HR if it isn’t high already

Cardiogenic shock 2/2 MI - ASA, antiplatelet, anticoagulation

Revascularization is essential!!! Valuable even if delayed.

Thrombolysis works poorly

THINGS TO AVOID:

Anything nephrotoxic - NSAIDs, ACE/ARB

DO NOT suppress sinus tach since this is usually compensatory and keeping the patient alive

Avoid diltiazem in afib with DHF

Do NOT treat mild stable hypoNa with hypertonic or salt tablets

Fluid and sodium restriction actually haven’t shown benefit in RCTs once they are in decompensated HF

BEWARE BETA BLOCKERS - don’t start them in decompensated heart failure

Great for chronic compensated HF

Negative inotrope could impair cardiac function

Controversial if BB should be continued in patients who are already taking them -- in general should be held in cardiogenic shock

References

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/649270

jamanetwork.com

Background Few studies have prospectively and systematically explored the factors that acutely precipitate exacerbation of congestive heart failure (CHF) in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Knowledge of such factors is important in designing measures to prevent deterioration of...

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4878602/

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Heart failure is a disease with high incidence and prevalence in the population. The costs with hospitalization for decompensated heart failure reach approximately 60% of the total cost with heart failure treatment, and mortality during hospitalization ...

https://emcrit.org/ibcc/chf/#hemodynamic_evaluation_&_risk_stratification

Forrester classification

Forrester classification - management

Stevenson classification