This POD was inspired by a case that Dr. Zerzan had in the Peds ED. An 8 year old with a traumatic injury presented with hip pain and was found to have an isolated posterior hip dislocation…

Hip dislocations!

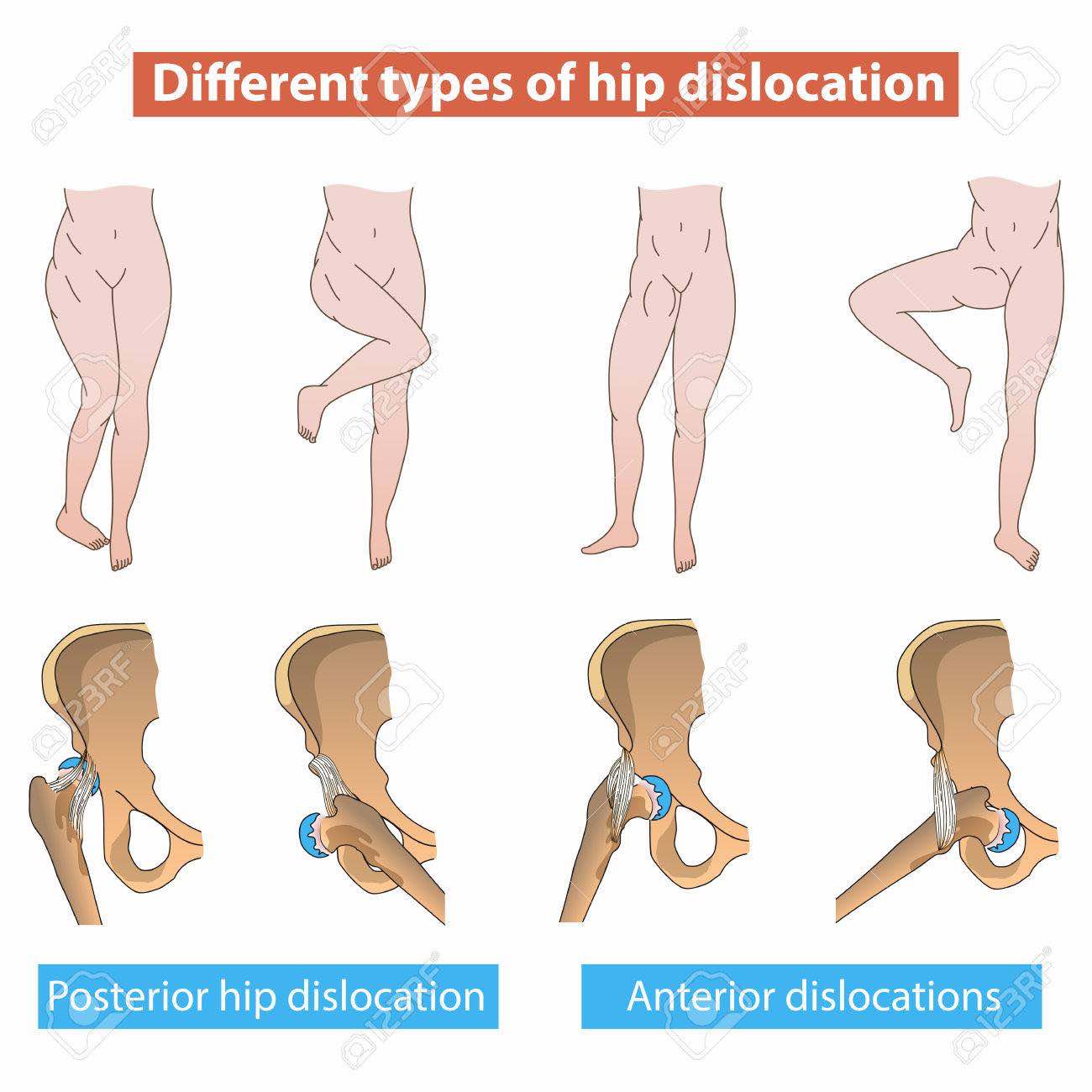

Posterior hip dislocations (PHDs) are far more common than anterior hip dislocations

(90% - 10%). This holds true in pediatrics as well in adults.

In a posterior dislocation, the patient presents with the extremity internally rotated and shortened.

In anterior dislocations, patients typically present with extremity flexed, abducted, and externally rotated.

We will focus on

posterior dislocations.

Classic presentation is with an axial load such as a knee hitting the dashboard in an MVC or other high energy mechanisms.

Important point: in adults and children >10yo, PHDs require a high energy mechanism and will often have several associated injuries.

However in children <10yo, PHDs can be seen in lower energy mechanisms such as routine sports injuries which is why you may actually see an isolated hip dislocation in a child. There are also fewer associated acetabular fractures in pediatric PHDs than adult PHDs.

Any child PhD knows…

..that PHDs are true emergencies!

You need to

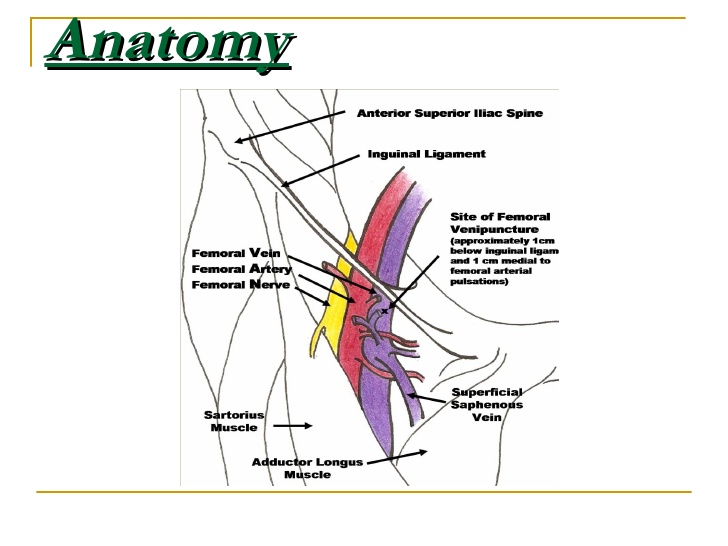

get it reduced ASAP (within 6 hours)

to prevent complications of femoral head osteonecrosis and sciatic nerve injury. Other complications include post-traumatic arthritis, and in pediatrics, physeal injury. Incidence of recurrent dislocation is higher in pediatrics than in adults!

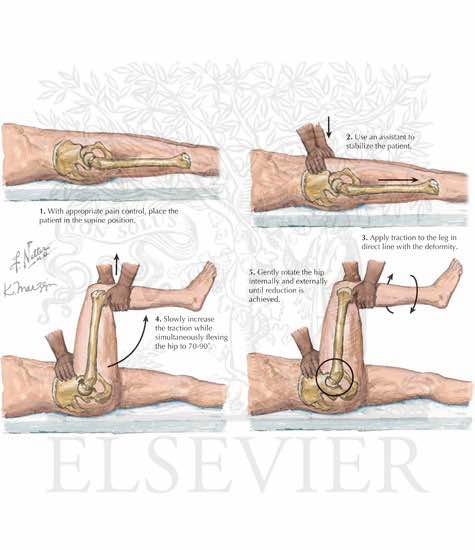

Reduction techniques:

The Allis Maneuver:

The Captain Morgan:

Video here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=82&v=lQMWaFX-MeQ

Propofol is preferred agent for procedural sedation given its muscle relaxant properties if it is going to be reduced in the ED, but pediatric cases are often reduced in the OR to ensure optimal muscle relaxation and to have more options available.

It is essential to have optimal muscle relaxation in pediatrics as the growth plates can be damaged during reduction.

Open reduction should be considered if fracture-dislocation or unsuccessful closed reduction attempt.

All patients should get at least a CT to evaluate for femoral head fractures, intra-articular loose bodies/incarcerated fragments, acetabular fractures.

Children should get an MRI to evaluate for ligamentous injury as well.

If closed reduction is successful, disposition is protected weight-bearing 4-6 weeks, ortho follow up.