The direct cause of angioedema is a loss of vascular integrity, which causes localized fluid shift from the blood into swelling in the tissue, hence “angio à edema.” Unlike your typical edema, angioedema tends to be non-pitting and is not gravity dependent.

In general, angioedema can be classified to 3 categories:

Histamine-mediated

Treat w/ antihistamines, steroids, epinephrine

Bradykinin-mediated

Can treat w/ fresh frozen plasma, C1 inhibitor concentrate, or some fancy bradykinin pathway inhibitors.

Will not respond to epinephrine, steroids, or antihistamines.

Other/unknown causes

For your critical patients, assume it is histamine mediated and treat with epinephrine empirically because the histamine pathway is more common, and the swelling tends to worsen very rapidly.

Histamine-mediated

Pathophysiology

Most commonly caused by allergen exposure causing IgE activation

Initial exposure to allergen à sensitization and plasma cell formation à repeat exposure à IgE mediated mast cell activation and histamine release

Some medications cause generalized mast cell activation

Opioids and radiocontrast dyes can do this

Will have severe reaction, even on initial exposure

COX inhibition

Caused by NSAIDs

Drives precursor molecules towards formation of leukotrienes à mast cell activation and histamine release

Bradykinin-mediated

Pathophysiology: Disruptions to kinin pathway cause increased concentration of bradykinin, leading to angioedema1. This is caused by 2 mechanisms:

Too much production of bradykinin

Hereditary/acquired angioedema causes too little functional C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH), which normally regulates bradykinin formation. This essentially releases the breaks and allows uncontrolled bradykinin formation.

TPA leads to increased bradykinin precursor as well.

Too little breakdown of bradykinin

ACE inhibitors prevent ACE from breaking down bradykinin

How do I tell what type of angioedema my patient has?

Testing for C1-INH is not useful in ED due to long turnaround times.

Histamine-mediated

Tends to be more acute and shorter lasting.

Usually caused by exposure to allergen

Bradykinin-mediated

Is not usually itchy

More commonly affects gastrointestinal mucosa, causing GI symptoms

Can be caused by stressor to body – i.e. surgical/dental procedure, infection, emotional stress.

ACE-inhibitor mediated. 43% occur within first month of treatment, although can happen years into the course.

TPA-mediated usually occurs in conjunction w/ ACE-inhibitor use.

Treatment

Follow normal ABC pathway

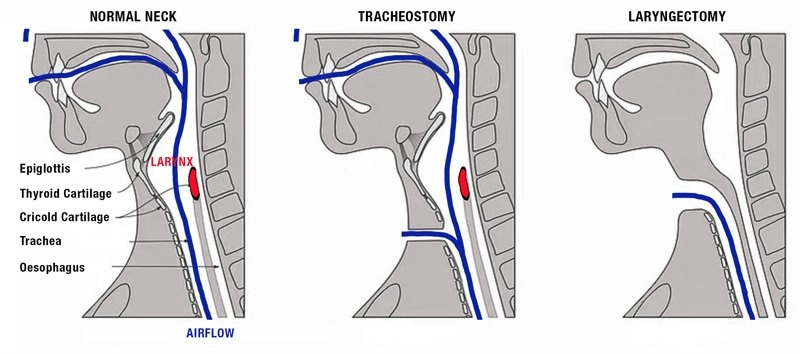

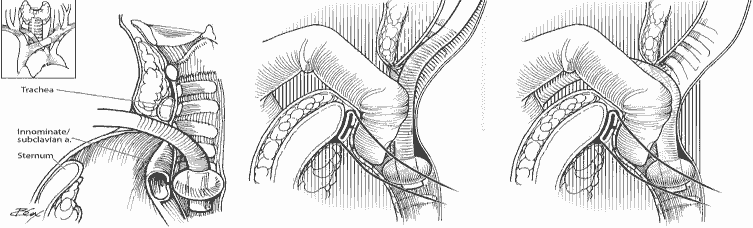

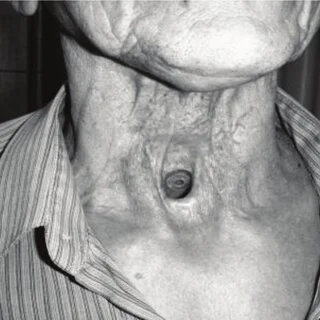

Airways can rapidly deteriorate. If intubating, you should have dual setup for surgical airway. Consider awake fiber-optic intubation in airway allows.

Fluids and pressors as needed for shock

In critically ill patients, follow the histamine-mediated pathway first because this pathway will have patients deteriorate more rapidly.

Histamine-mediated angioedema

0.3-0.5mg IM epinephrine (1mg/ml)

0.01mg/kg for pediatrics

Repeat q5-15min PRN up to 3 doses

Consider epi drip if refractory

In patients on beta-blocker, consider glucagon 1-5mg IV push, then 1-5mg/h infusion, to bypass beta-blockade.

Antihistamines

Benadryl, Pepcid

Steroids

Thought to reduce biphasic reactions, though recent studies are starting to question this2.

Bradykinin-mediated

Fancy drugs

Replacement options for C1-INH. These are plasma derived human concentrates.

Berinert – FDA approved for acute intervention

Cinrynze – FDA approved for prophylaxis only

Kallikrein inhibitors to cause decreased bradykinin production

Ecallantide

Block bradykinin receptors

Icatibant

Fresh frozen plasma, 2 units.

Will have physiologic levels of C1-INH, replacement ACE (a.k.a kininase II). Physiologic concentrations are much lower concentrations than the fancy drugs above, so requires larger volumes3.

Paradoxically, will also have physiologic levels of bradykinin and may have autoantibodies to C1-INH that can make angioedema acutely worse4. Case studies suggest this is rare, but be ready to intubate!

References

1. EM:RAP CorePendium. EM:RAP CorePendium. Accessed December 22, 2023. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recgmcfxPSDNkQRTU/Angioedema

2. Lewis J, Foëx BA. BET 2: in children, do steroids prevent biphasic anaphylactic reactions? Emerg Med J EMJ. 2014;31(6):510-512. doi:10.1136/emermed-2014-203854.2

3. Chaaya G, Afridi F, Faiz A, Ashraf A, Ali M, Castiglioni A. When Nothing Else Works: Fresh Frozen Plasma in the Treatment of Progressive, Refractory Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor–Induced Angioedema. Cureus. 9(1):e972. doi:10.7759/cureus.972

4. Long BJ, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Evaluation and Management of Angioedema in the Emergency Department. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(4):587-600. doi:10.5811/westjem.2019.5.42650